What’s Old Is New

Among the overflowing shops that make up Denver’s Antique Row stands a sophisticated studio dedicating to reimagining and repurposing rare, vintage and, yes, antique finds.

WRITTEN BY Amy Speer

Tucked away among a scattering of antique stores, you’ll find that an interior world filled with vintage oddities, dripping chandeliers and ornate furniture exists in a bustling Denver neighborhood.

The 23-year-old shop — Watson & Co — is part design studio, part antique store and every bit sophisticated. The store is located on South Broadway in Denver’s famous Antique Row, a seven-block strip filled with more than 100 antique merchants.

Watson & Co isn’t a heap of mismatched antiques. Rather, it’s a blend of high-end wholesale furniture with carefully selected vintage pieces, all meticulously staged in small, quaint rooms.

At the studio, owner Chris Watson loves mixing the old with the new — mixing being the key word in what Watson describes as the latest interior design trend.

You don’t have to go overboard on the French château look. With the right blend of urban funk or a sprinkling of other inspirations, an interior home décor can be more dynamic nowadays.

“That Ralph Lauren home collection era, where everything used to match in the 1990s, is long gone,” Watson says.

For instance, you can take a traditional French chair from the 1930s, cover it in cowhide and create something unusual.

“It’s about reinventing it,” Watson said. “It’s about creating the unexpected.”

Other shop owners along Antique Row will be quick to point out that Watson’s wares aren’t truly authentic.

But that’s okay, Watson says. It all depends on how you define authentic.

In fact, Watson doesn’t even like using the word “antique.” He prefers “vintage.”

“The word antique makes it feel exclusive, like something you can’t afford,” Watson says. “People want to be a part of something, instead of separate from something.” And with a good mix, you can have the best of both worlds.

A few authentic treasures blended into the décor become just that — treasures. And conveniently, Watson sells those authentic treasures next door in his south location, appropriately dubbed The Annex. Here, it even smells different from the design studio. Brittle paper, musty furniture and old wood create a nostalgic atmosphere. And every corner, carefully staged, is filled with some vintage curiosity.

A 1910 photograph of Denver firefighters sits behind glass. On the floor, a handful of 1911 anatomy posters leans against a stack of more framed oddities. A brittle wicker cage once used to transport family pets sits on top of an old cabinet. Here, the real treasures wait to be plucked away by a walk-in customer or by one of Watson’s three interior designers.

The most unique item Watson ever sold — online because it was so rare — was a condom tip from early World War I. Made out of lamb intestine, it was neatly package in a metal tin. Watson had snapped up the rarity, along with an 18th-century bible, in the same morning.

In the end, after 23 years of selling antiques, Watson has discovered what makes this business tick. “Americans yearn for history,” Watson says. “People just want to feel connected to something.”

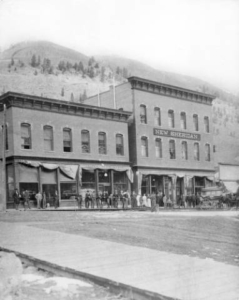

One Man’s Trash

Picking through American keepsakes on Denver’s Antique Row

Like tasty little sprinkles on a cupcake, Antique Row on South Broadway offers a scattering of sweet little shops on a busy street populated by liquor stores, tattoo parlors, thrift shops and even an abandoned Sinclair gas station.

Under welcoming awnings with clever names, such as Finders Keepers, All Hours and Flashback Jack’s, these stores offer a portal into another time.

Denver Hotel Magazine took a day to wander in and out of the shops that specialize in some unique history. Here are some of our favorites:

Heidelberg Antiques

1460 S. Broadway

Featuring European furniture and mountain-home accessories, this shop is filled with Black Forest carvings, antler furniture and antique linen for a country look. The store’s most interesting offering, perhaps, is its massive cowbell collection that hangs from the ceiling. Shelbey Adame, who works on the weekends, says this is the most authentic antique shop you’ll find on the block. “It’s not an antique if it’s not 100 years old,” Adame says. “Anything less is vintage.” And you won’t find that here.

The Broadway Antique Broker

1438 S. Broadway

If your man cave is in need of a classic backroom bar, this is your place. But be sure you have the space to accommodate something massive. These ornate bars come in every shape and size. Ken Barnes, owner for 25 years, began specializing in bars 10 years ago after he sold one for $40,000. Small bars now run anywhere from $7,000 to $10,000. Larger bars can run upward of $60,000. Barnes, fondly known as Backbar Barney, plucks these historical finds from every corner of the country.

Antique Broker

1438 S. Broadway

Above Backbar Barney’s, up a flight of paint-chipped stairs, a whole other world awaits. This has been Al Garcia’s world since 1971. Garcia fills it with just about anything he can find. A hoarder’s dream, the cluttered atmosphere will tug at your heart strings. Handmade signs flutter precariously from strings with the words “Look Up” written on them. There, any oddity that Garcia can hang dangles from the rafters. If you’re treasure hunting, this place might be where you discover that hidden gem.

Frontier Gallery

1452 S. Broadway

If you’re expecting to find a little Western flare on Antique Row, you won’t find much — unless you pop into Frontier Gallery. There, amidst a line of stores that specialize in most any European antique, this store is as Old West as it gets. It’s a six-shooter’s dream, in other words. Dubbed Colorado’s only antique firearm store, Frontier Gallery features genuine Western-era Colt pistols, Winchester rifles, Civil War weapons, Western memorabilia and Indian artifacts.