The townspeople of Telluride protect and celebrate the area’s rich history full of tall tales through the tradition of oral storytelling.

written by JULIE PIOTRASCHKE

On any given morning in the shadow of the San Juan Mountains, you can find Telluride resident Ashley Boling at home getting ready for his day in town.

He pulls on a rugged pair of blue jeans, snaps the buttons close on a heavy cotton work shirt and ties a red bandanna around his neck. He even slips on leather work boots — similar to those the miners in the nearby peaks used to wear over a hundred years ago. And he adds the last detail — a dusty cowboy hat perched on his head.

Boling’s outfit isn’t too out-of-the-ordinary for the mountain town of Telluride. But in this case, his accessories are necessary for his trip back in time as one of Telluride’s oral storytellers.

His destination is the San Miguel County Courthouse in downtown Telluride. The red brick building with its three-story clock tower rises above all else on West Colorado Avenue, commonly known as Telluride’s Main Street.

That’s where he starts his storytelling. A group of tourists, students and residents gathered learn that behind Telluride’s well-kept Victorian facades are rich stories of Southern Ute Indians who roamed the surrounding hills, a boom-and-bust mining town with accompanying Wild West tales and a city that made major contributions to the country’s emerging industrial scene.

“Our town is significant in our nation’s history just like any battlefield in the South, or like the old part of Boston,” George Greenbank will tell you. Greenbank has lived in Telluride for 42 years, is a practicing architect and a student of history, he likes to say.

Greenbank and other storytellers will take you on a journey back to much quieter times — a stark contrast to the friendly bustle that now greets visitors who come for the world-renowned ski resort and popular summer festivals.

The town, nestled below the peaks of the Uncompahgre National Forest, was uninhabited until the winter of 1872. The Ute Indians had used the area

as their seasonal hunting grounds but found the weather at 8,750 feet too harsh. “They couldn’t get things to grow here,” Boling explains. Telluride’s average temperature in the winter hovers around the 20s with yearly snowfall piling up around 300 inches.

So the valley remained quiet until 1875 when the first gold was found in the nearby mountains. The discovery sparked a small mining settlement. They called it Telluride, named for the eagerly anticipated tellurium elements to be mined from the mountains. Ironically, tellurium would never be found in the area.

Like most mining towns, there were wild boom times. At the turn of the century, more millionaires per capita lived in Telluride than in New York City. The town’s population had soared from just a few dozen to 5,000 as more than $360 million of gold was pulled out of the surrounding mountains. Zinc, lead, copper and silver were also in abundant supply. The new Rio Grande Southern Railroad established a depot in Telluride, offering efficiency and replacing slow burros that had to zig-zag up the steep mountains with supplies. Trains quickly followed, full of immigrants from Western European countries claiming to be experienced hard-rock miners hoping to snatch up some much-needed, plentiful work.

Good times were so abundant that a young Butch Cassidy took notice. Along with a sidekick, Cassidy robbed his first bank in Telluride in 1889 — the San Miguel County Bank Main Street. He made away with $22,000 in cash, designated for the mining payroll. No guns were fired; no one was hurt. The money was never recovered.

Harsh conditions and increasing demands led to labor disputes between the mineworkers and owners. Unions were formed — most notably a local chapter of the Western Federation of Miners — and workers went on strike demanding to be paid $3 for an eight-hour day. Not all mine owners agreed to the pay increase. Tensions between the miners and owners rose until the leader of the local union, Vincent St. John, disappeared. The turmoil escalated until the Colorado governor sent in carloads of state militia to drive out the strikers. The men were dumped into a neighboring town and told not to come back. The back-and-forth struggle, replete with gunfights, bloody battles and casualties, went down in the state’s history as the Colorado Labor Wars.

“You could say the town lost its spirit during that time,” Greenbank says.

Still, the mining town continued to thrive, quickly emerging on the national scene fated to play a major role in the development of electricity.

The manager of the Gold King Mine, Lucien L. Nunn, needed to reduce the mine’s operation costs. He saw the mine’s monthly coal bill of $2,500 and decided to replace coal with a new alternative source of power — electricity.

He looked to electrify his mine at the same time Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla were locked in their now-famous “Battle of the Currents.” Edison promoted direct-current electricity, which cannot travel long distances; Tesla supported the alternating current he developed, which could. Both believed their method superior for widespread use.

Nunn’s involvement and Telluride’s geography decided it.

The needed power had to travel a few miles between the jagged mountainside and the mine, making Tesla’s alternating current preferable. He built what would be known as the Ames Power Plant, the first alternating-current plant, near Telluride. A sight new to many appeared: powerlines, the first built in the nation.

The Ames Power Plant brought power to the Gold King Mine in 1891 and provided the first transmission in the world of long-distance, high-voltage alternating current for commercial purposes. It also gave Tesla and his partners the success they needed. Invited to demonstrate alternating current at the World Fair in 1893, they literally lit up the fairgrounds — and the future. Today, electricity is transmitted to our buildings and houses through alternating current.

While the lights never dimmed on Telluride’s power plant — it remains a working plant — they did in the mines, and eventually in the town.

“In the ’60s, we were nearly inducted into the official Colorado Ghost Town Hall of Fame,” Boling says.

You wouldn’t know that today by looking at the picturesque, thriving community.

But the residents of Telluride are working to make sure that those who do make it to this Southwest hub know the stories that have created its richness.

In 1964, the town worked tirelessly to get the downtown core of Telluride designated a National Historic Landmark District. Designated by the Secretary of the Interior, Telluride’s downtown joined the fewer than 2,500 historic places with the distinction. It also is one of Colorado’s 20 National Historic Landmarks.

That designation comes with strict building guidelines regarding the preservation of historical structures. It has imbued the community with an understanding of the importance of the town’s history and the difficulties that preserving it entails. Just the approval of construction plans can require years of revisions and plenty of investment.

“Our town accepts the responsibility and stewardship of our historical district,” Greenbank says. “We know it’s important, and it’s part of our culture. When we go out of our way to preserve the buildings, we need to celebrate that. I really try and raise our history and what we’re doing here to a level of celebration.”

In addition to the ongoing walking history, architectural and cemetery tours, the Telluride Historical Museum offers educational sessions throughout the year focusing on different aspects of the town’s past.

They have five self-guided tours available for purchase and download and have placed plaques throughout town that offer insight into the importance of Telluride in world history. The storytelling tradition even travels up the mountain. Up at the Telluride Ski Resort, one can find Boling leading Ski into History Tours that take off from the Peaks Resort and Spa during the winter. Fireside chats featuring writers, historians and scientists discussing Telluride’s past are held by the Historical Museum regularly.

“Sharing our history is a pretty integral effort,” says Lauren Bloemsma, who worked as the director of the Telluride Historical Museum for seven years.

Or you can wait for Telluride’s history to find you.

“Whether you are sharing a gondola at the ski resort or having coffee on Main Street, people here love to share the history of the town,” says Bloemsma. “People here are very passionate, and that includes being passionate about their sense of history.”

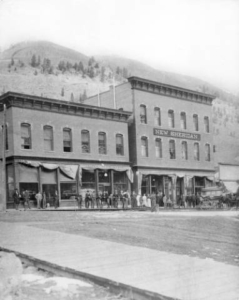

Business owners such as Michael Gibson of the Appaloosa Trading Company will gladly point out Popcorn Alley, where the brothels in the Red Light District were. He will tell you the New Sheridan Hotel has its original 1895 fixtures and that the Sheridan Opera House — built in 1913 — was the last commercial structure built in Telluride until 1973.

When Boling is finished with his tour, he heads home and sheds his cowboy gear.

And he revels in the thought of doing it all over again. And again.

“I always feel really good after a tour,” he says. “I feel that I’m sharing knowledge and providing an understanding of what’s happened here.”

And with a tip of his hat, he says he’s hoping that the next tour is as soon as tomorrow.